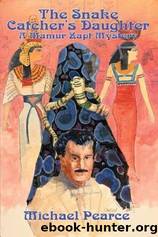

Mamur Zapt 08 The Snake Catcherâs Daughter by Michael Pearce

Author:Michael Pearce [Pearce, Michael]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: det_history

Published: 2014-07-15T13:16:26.559330+00:00

âA lot of nonsense,â said Owen, when they were alone.

âIs it?â said Mahmoud.

âYes,â said Owen, âit certainly is.â

âIâm not so sure,â said Mahmoud. âGarvin is an ambitious man.â

âIt wouldnât have been Mustapha Mirâs job that he wanted,â Owen pointed out. âIt would have been Wainwrightâs.â

âAnd he got it,â said Mahmoud.

âThat was later. That was nothing to do with this.â

Mahmoud, however, looked thoughtful.

âThere are obvious weaknesses in the story,â said Owen.

Mahmoud nodded.

âYes, but I will have to check them. I will have to investigate his accusations too, though.â He looked at Owen. âThat means going through the files.â

âWhose files?â

âYours, perhaps,â said Mahmoud. âOr rather, Mustapha Mirâs.â

Owen was silent. There was a lot of secret material in the Mamur Zaptâs files. Would the Administration agree?

âMore to the point,â said Mahmoud, âI shall have to go through the Commandantâs files. Did Wainwright authorize Mustapha Mir to conduct an investigation into corruption in the Police Force? If he did, there ought to be some reference to it in the files.â

âGarvinâs sitting on those files now,â said Owen.

âI shall have to ask him to release them.â

Owen was silent again. Garvin, he felt sure, had nothing to hide, but he might well object to opening his files to the Parquet. It was the principle of the thing, he would say. The Commandant of the Cairo Police was such an important post that its incumbent was appointed directly by the Khedive, not by the Minister of Justice. There was a reason for that. The Ministry was responsible for the administration of justice; but the Commandant was responsible for maintaining order, and the Khedive cared a lot more about maintaining order than he did about justice.

It could be put, too, another way. The Khedive appointed the Commandant on the direct advice of the British Administration, and the British were even more interested in maintaining order than they were in the administration of justice. The niceties of the legal administration they were quite happy to leave to the Egyptians; the exercise of power, though, they wished to keep to themselves.

The British Administration was advisory only. In theory, the Khedive and his ministers could reject that advice. In practice, because of the Egyptian Governmentâs financial dependence on Britain, and because of the large British army stationed in Egypt, the advice was not something the Egyptians could easily disregard.

The British were punctilious in observing the advisory form. On the one hand it gave them something they could shelter behind; on the other, it saved the Khediveâs self-respect.

Up to a point. As the years went by, and memory of the financial crisis receded into the background, the Khedive became increasingly restless. So did ambitious ministers. And so, much, much more so, did the growing forces of Egyptian Nationalism. There were many now, especially among the young professionals, who were eager to challenge the advisory form, to bring matters to a head over whether the British were here as advisers only or whether they were here to rule by force. The young lawyers of the Parquet, for instance.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Spy by Paulo Coelho(1617)

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese(1599)

Cain by Jose Saramago(1534)

La Catedral del Mar by Ildefonso Falcones(1163)

The Prince: Jonathan by Francine Rivers(1157)

Bridge to Haven by Francine Rivers(1145)

The August Few Book One: Amygdala by Sam Fennah(1115)

La Catedral del Mar by ILDEFONSO FALCONES(1072)

La dama azul by Sierra Javier(1057)

Cain by Saramago José(1049)

La dama azul(v.1) by Javier Sierra(1036)

A Proper Pursuit by Lynn Austin(1027)

Quo Vadis: A Narrative of the Time of Nero (World Classics) by Henryk Sienkiewicz(1023)

Devil Water by Anya Seton(1004)

Sons of Encouragement by Francine Rivers(977)

The Sacrifice by Beverly Lewis(973)

The Book of Saladin by Tariq Ali(964)

Murder by Vote by Rose Pascoe(944)

Creacion by Gore Vidal(929)